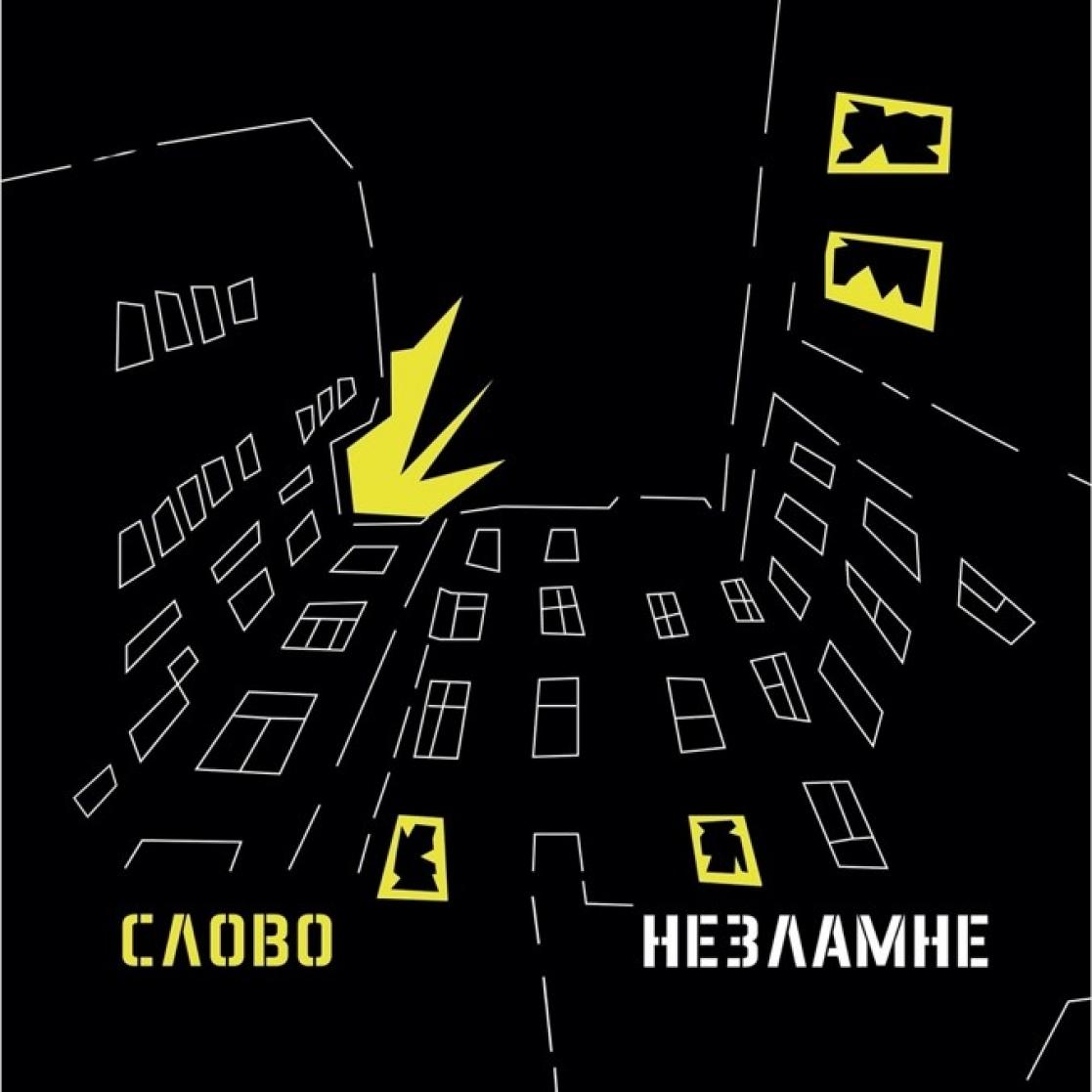

#ARTvsWAR | The Word is Adamant: the struggle for existence of Ukrainian literature

Photo credit Ukrainer. Original source: https://www.instagram.com/p/CGrwwzEgEYL/

At the beginning of 1920s, there was a trend for contemporary Ukrainian authors of that time to relocate to Kharkiv, a dynamic and vibrant city full of new ideas, interesting events and professional opportunities. Networking, social life and romantic inspirations attracted young talents from the countryside and even from other cities including Kyiv. Yet, the living conditions were harsh – communal apartments, shared rooms with few beds or simply sleeping spots in the storage room of the editorial office were common solutions. Reading memoirs of that era, we come across episodes of sleeping on the floor covered with newspapers and keeping manuscripts inside cooking pots to have them protected from rodents.

The idea to ask Soviet authorities to provide housing for bright representatives of Ukrainian literature that appeared in the writers’ community was supported, although not without effort. In 1929 the newly designed and constructed building accommodated 66 families of Ukrainian authors in the apartments which were close to luxury by the standards of that time.

Yet something that might sound like the beginning of happy and productive creative life became a symbol of Executed Renaissance. The house very quickly turned into a place of denunciations, prosecution, spying, repressions and suicides caused by the pressure of the Soviet system.

Great Purge with its arrests and mass executions is a very convincing proof of the idea of “denazification” (which de-facto is the elimination of Ukrainian people) is rather a cruel tradition than an invention of the Russian propaganda in the context of the ongoing war that started in 2014. Ukrainians had to struggle for their own existence and for the existence of their culture for centuries.

In the course of Soviet history, the building lost its connection to the literature scene and was populated by different families that received the apartments of repressed authors from the state. The stories of the previous inhabitants were not something to talk out loud about, so for decades names of the authors once living in the house were forgotten and their texts were prohibited.

Hundred years later

But now these writers are remembered and widely read, they gain on their stolen fame as their prose and poetry sparkle with vitality and open-minded views but not with the nationalism most of them were accused of. Their only fault most often was writing in their native Ukrainian. If you could walk around the building right now on one of the corners, next to the sign KULTURY str., you would find a handwritten note “My culture was executed”.

But in 2018 the first attempt to compensate for historical injustice was made. Kharkiv Literature Museum together with PEN Ukraine has launched a writers’ residence in one of the apartments of SLOVO BUILDING which was bought by sponsors, especially for this purpose. The address immediately became an inspiring destination for contemporary writers from all over the country and from abroad.

Bandy Sholtes from Uzhhorod, which is 1300 km away was the first one to stay at the residence for a month and that is what he said about his stay:

When I was planning my trip to the Kharkiv writers’ residence I have been thinking it is all about literature. But it appeared it is much more about Kharkiv. After spending a month here I fell in love with the city and its people. I immediately felt like home. The city has opened to me, absorbed me, protected me. I could have never thought I would say something like that but after first two weeks I had the feeling I could actually move to Kharkiv. Living here is like deconstructing the myth, turning people from the textbooks back into flesh. You go to the kitchen and it just comes down on you – here, just like you, they were frying their steaks, smoking their morning cigarettes, having loud parties. They were just living. And then you start feeling their dark shadows behind your back, start thinking of all the horrors we should make sure will never happen again.

The residence was functioning during difficult times of pandemics – the safety measures were challenging but following these rules helped to keep the continuity of the mesmerizing rebirth of the metaphoric fireplace of Ukrainian literature that was suspended for almost a century.

But horrors came to Kharkiv again and the war does not obey any rules.

Since the 24th of February 2022 when Russia stated its full-scale atrocious assault on Ukraine under the false pretence of “denazification”, Kharkiv became one of the cities under severe attacks and missile strikes. Schools, museums, hospitals, churches, administrative and residential buildings – everything became a target of brutal bombings.

On March 8th, Russian shelling damaged the facade of SLOVO house. As Kharkiv (along with Mariupol and Chernihiv) remains the target of non-stop brutal artillery fire from the Russian army, the fate of the building along with many other historical landmarks remains uncertain. The object is listed among Russia’s war crimes that caused the destruction of Ukrainian cultural heritage.

THE WORD IS ADAMANT

But despite all the context social media activity of the residence SLOVO gives a lot of hope and prove that Ukrainians are not going to give up and will not let Russia put the development of the culture on standby again. Especially when there is the support of international partnerships in Europe and overseas.

For example one of the posts from Audrey Rosey, who was to become a resident in 2022, states:

Because of the current war on Ukrainian soil, the artistic residency at Slovo House in Kharkiv, Ukraine is temporarily on hold. As an artist that was scheduled to come create at Slovo House this September and October, I am more than sad about the situation. And in the midst of all the destruction, I would like to do what I can to continue to cultivate creative energy in the interest of Ukraine until we can rebuild Slovo.

Now Audrey invites Ukrainian artists to come and participate in a fully covered residency with her in Pittsburgh which is the international sister city of the Ukrainian city of Donetsk, that has been occupied since 2014. The project is based on the works of Mykola Khyvlovy – one of the writers from the Executed Renaissance generation who helps to build the continuity of Ukrainian culture from the 1920s to the 2020s.

These days, Ukrainian writers, artists, musicians and workers of cultural institutions actively participate in defending their country, their culture, their language and their existence by all possible means (PEN Ukraine video).

Background

This story is part of the #ArtVsWar campaign. It aims to raise awareness of the level of destruction of cultural heritage, art objects, suspension of cultural life and initiatives due to war conflict. In Ukraine and for Ukrainians, their culture is today present due to the courage of a brave people capable of combating ongoing threats of its destruction.

Follow EEAS social media accounts to find more stories.